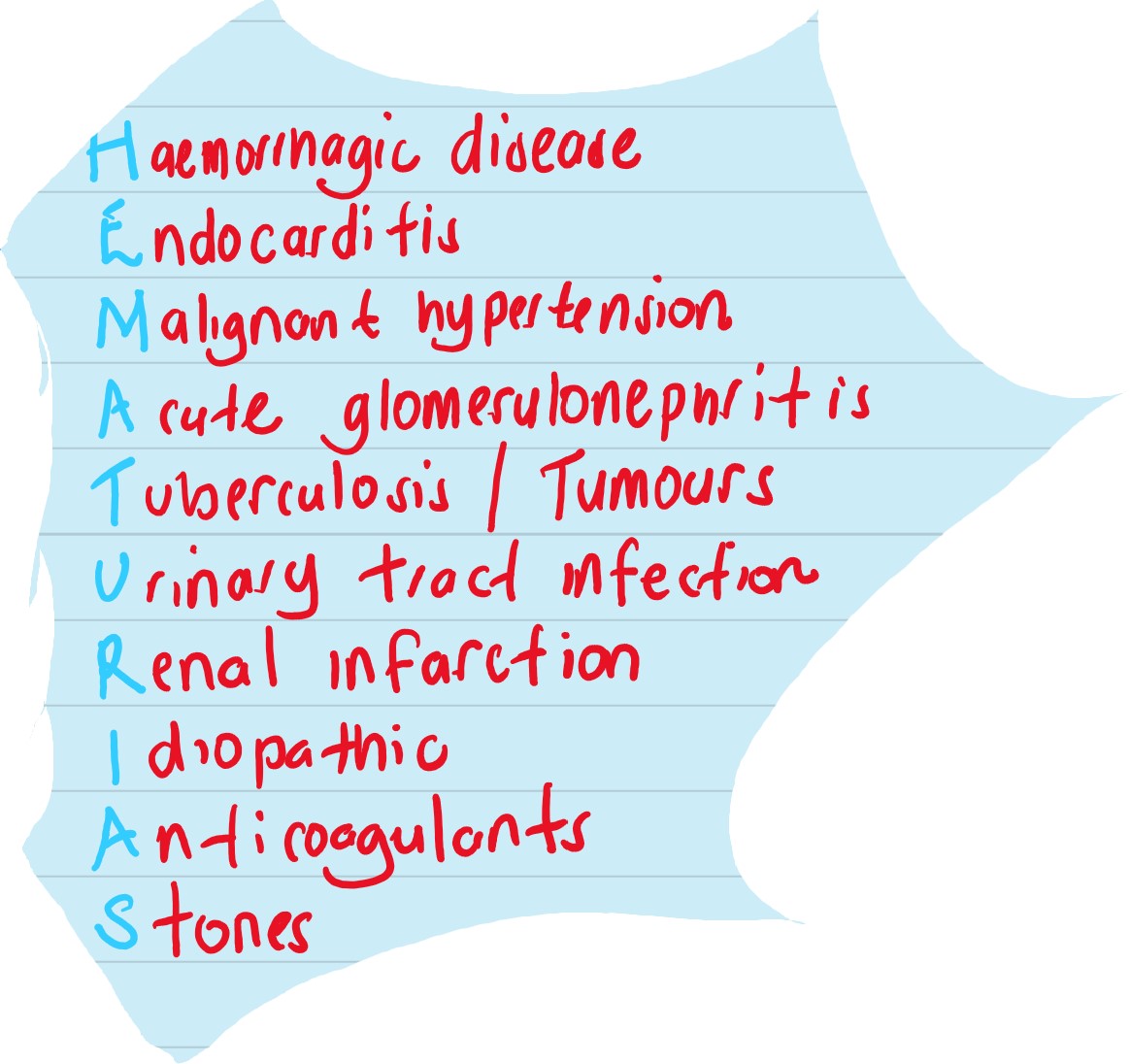

Haematuria (blood in urine) is a symptom of utmost clinical significance. On many occasions, the cause is elusive, yet several of these warrant a detailed patient history and examination to demystify them such that their diagnosis is not late. Today, we outline the diseases you should look out for when a patient presents with haematuria.

Haematuria can be visible (macroscopic) or nonvisible (microscopic) blood in the urine. We detect this symptom through patient history and laboratory examination. A patient may present with frank blood in the urine: or we may confirm this using urinalysis through urine dipstick, followed by microscopy to detect red blood cells (usually more than 2 or 3 per high power field).

When blood is present in urine, depending on the history, risk factors, and examination findings, several other tests can be conducted- for example, cystoscopy, imaging that included ultrasonography, Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans. More still, blood biomarkers can be requested to assess the presence of specific diseases, say bladder and kidney cancers.

Related:

Should we screen for kidney disease among people living with HIV taking Tenofovir-based ART?

The urogenital system comprises several organs and parts: kidneys, ureters, urinary bladder, and urethra, as well as the reproductive organs. It is prudent to classify such diseases according to the different possible sources of bleeding.

In many cases, trauma precedes haematuria. However, IgA nephropathy, Alport’s syndrome (familial nephritis), thin basement membrane disease, C3 nephropathy, and postinfectious glomerulonephritis constitute the glomerular causes of haematuria.

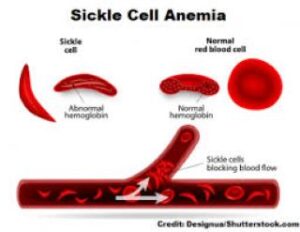

Non-glomerular aetiologies of blood in the urine include polycystic kidney disease, sickle-cell disease and papillary necrosis, nephrolithiasis (kidney stones), tumours, leukaemia (blood cancer), infections (pyelonephritis), and strenuous exercise.

Ureteral haematuria can be due to stones, infections, trauma, and tumours. Vesicular (bladder-associated) haematuria may be due to urinary tract infections, bladder stones, systemic infections, irritation, tumours, and foreign bodies. Haematuria originating from the urethra usually follows trauma and infection.

Prostatic bleeding, vaginal bleeding, and endometriosis of the urinary tract are other crucial causes of haematuria.

As you can see, the list is diverse; we don’t expect you to investigate the patient for everything. But we assert that you take thorough history and examination to delineate the most appropriate diagnosis. And if you cannot find one, be honest with the patient and plan a follow-up visit.

A fascinating paper at the NEJM explains the nitty-gritty of haematuria from investigation to diagnosis and practice guidelines. Read it.